The College today is the site of many kinds of work, both academic and otherwise, with chefs, gardeners, scouts, and numerous others contributing to the running of the College. Nowadays, nearly all of College work is carried out by human staff. For centuries, however, the College was home to an array of working animals, both those in the direct service of the College, and those raised commercially. The Industrial Revolution and the end of farming on College grounds have largely eliminated the presence of working animals in College, with the notable exception of the Harris hawk that is currently employed to rid the ancient tracery of pigeons.

Horses were evidently present from the very beginning of the College. They (or their more humble counterparts, donkeys and asses) no doubt would have been employed during the initial construction of the buildings, and the earliest versions of the Magdalen’s statutes drawn up by Waynflete make provision for their ongoing employment in the College’s business.

The College statutes dictate that the President should be afforded a “suitable number of horses…not to exceed six” for his business and the business of the Fellows and servants of the College, and that these and all their needs – bridles, saddles, and so forth, be provided by the College. The statutes further require that the President have a horse keeper to ensure their husbandry. Additionally, a seventh horse is provided for the Clerk of Accounts.

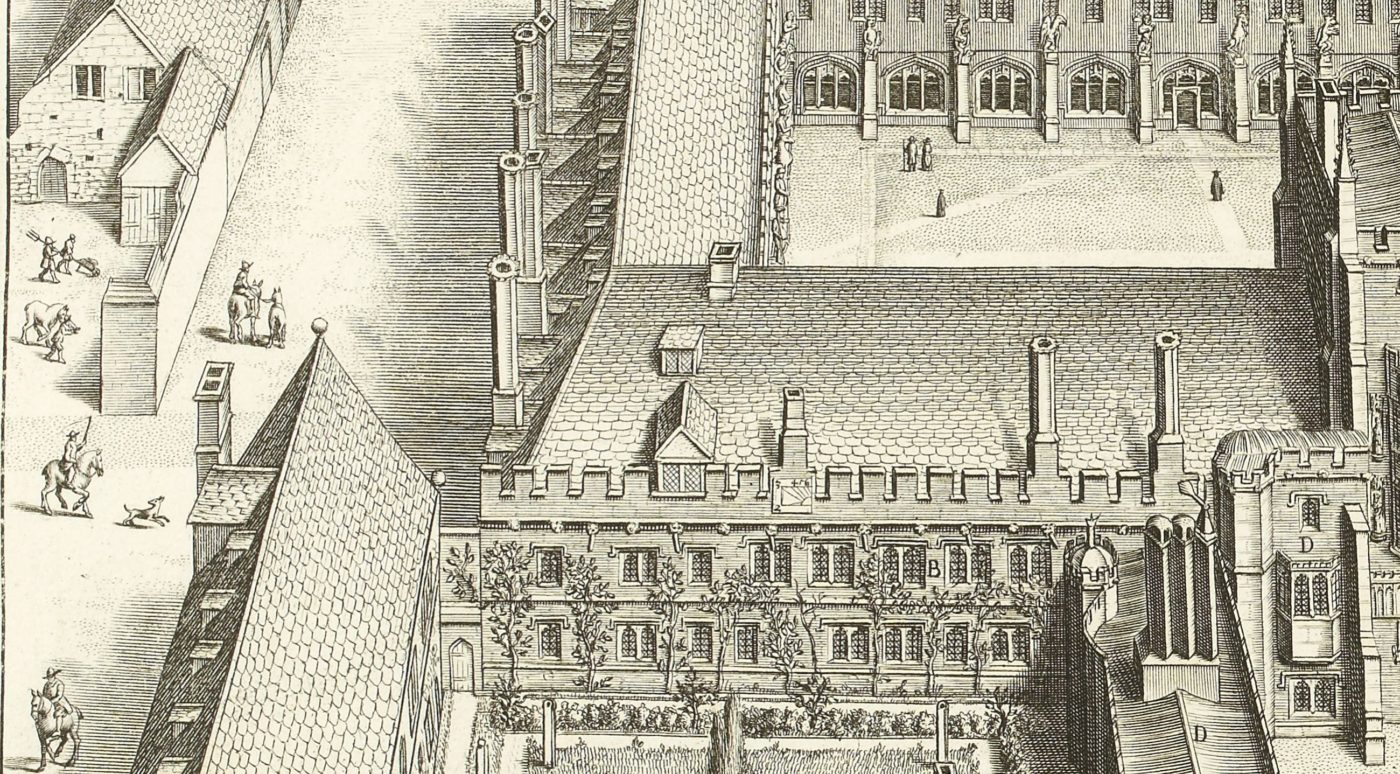

David Loggan’s collection of Oxford views, Oxonia illustrata, captured what is now the grounds of New Building in a completely different configuration in the last quarter of the 17th century. The top left-hand corner of this plate shows the north end of Cloisters where a yard of stables and work buildings were located, with several horses being led up and down the lane. These stables were taken down in the 18th century to make way for the New Building and its lawn. Image source Source gallica.bnf.fr / National Library of France

President Routh installed this stone pylon, still in position near the College gate through the Longwall, to aid in mounting his horses.

These provisions seem surprising now, but horses would have been in daily practical use for the majority of the College’s history, and the practicalities of their housing and use are reflected in depictions of the College site. Loggan’s view of the Magdalen shows a series of stables and other infrastructure running along the area behind Cloisters, which persisted in use until the New Buildings took their place. President Martin Routh, the College’s longest serving President, left perhaps the most permanent mark of the day-to-day labours of horses in Magdalen. The large stone pylon, now august with lichen outside Grove Quad, originally served as a mounting block, allowing the aging President to more easily mount his horse in the later decades of his 63-year Presidency.

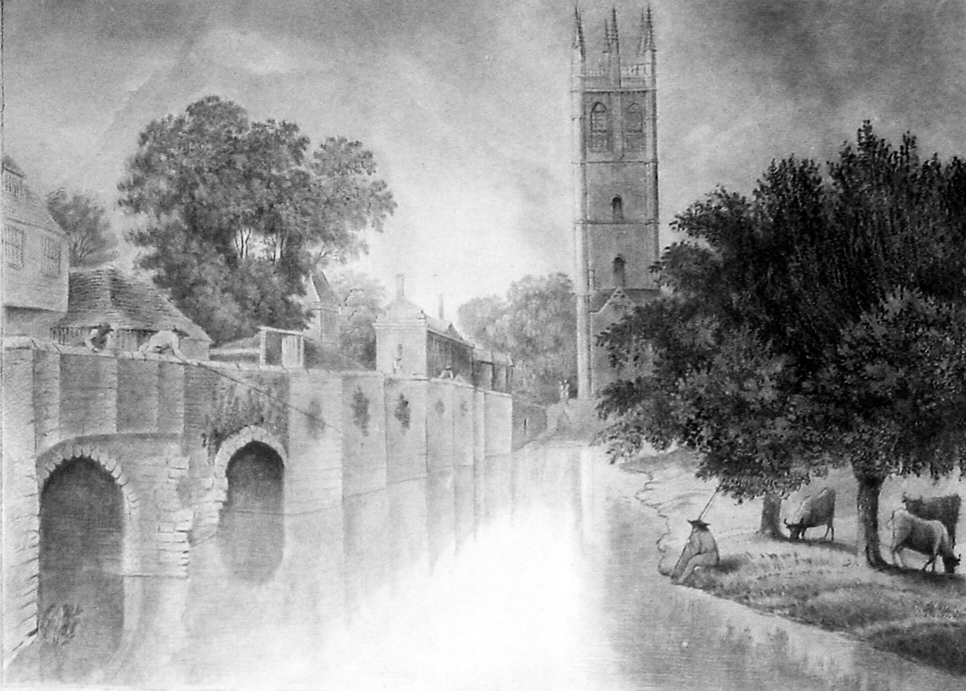

‘A view from St Clements of Magdalen Bridge, Oxford, before it was taken down in 1772’ by John Malchair, Magdalen College P1037

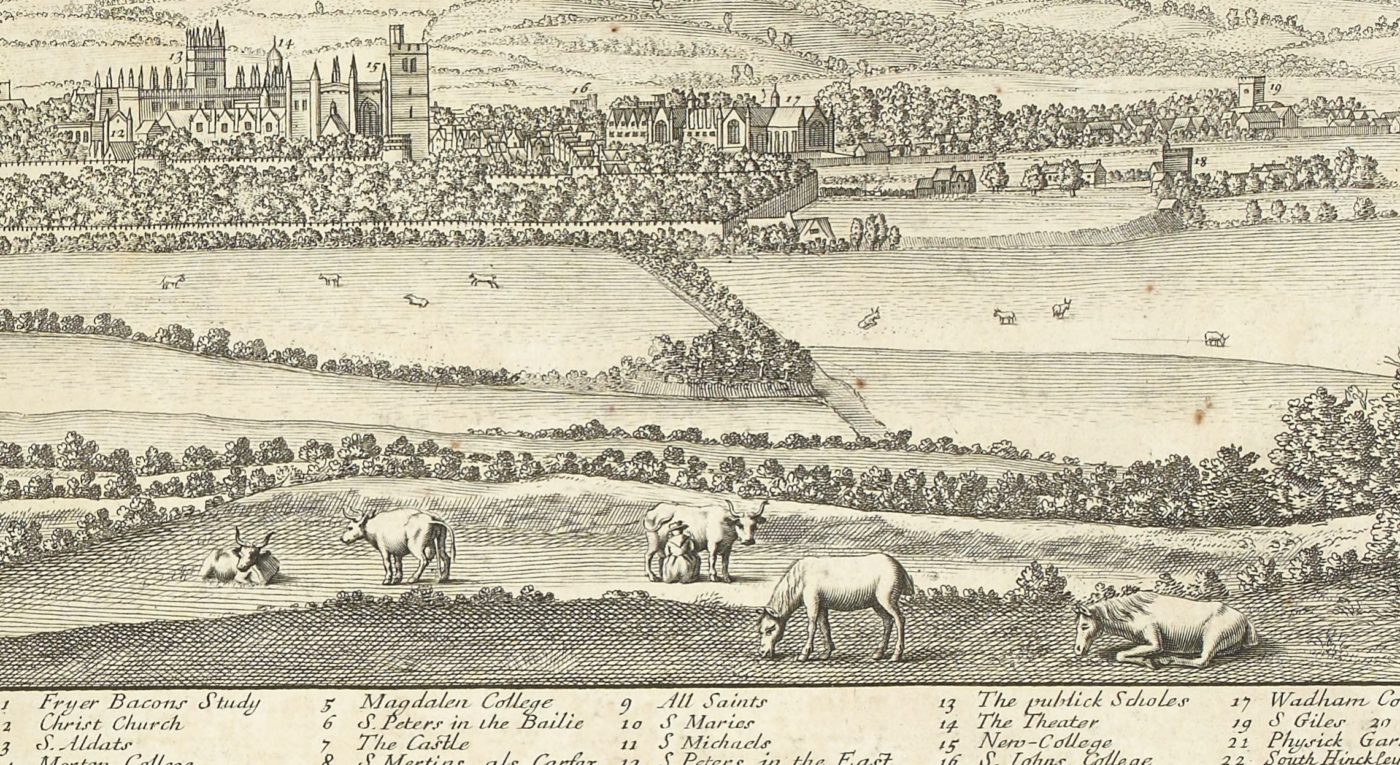

Water Meadow and Angel & Greyhound Meadow have been used to graze cattle from at least the late 16th century until the end of the 19th century. This pencil drawing, by John Malchair, which was the model for an engraving by E. Howorth, shows cattle on Water Meadow and an angler opposite the old Magdalen Bridge. There has been a bridge across the Cherwell since the early 11th century; the bridge depicted here dates from the 16th century and at several points in its history had houses and shops on both sides (as depicted here). The current Magdalen Bridge was completed in 1778 to a design by John Gwynn, and was widened in the 19th century.

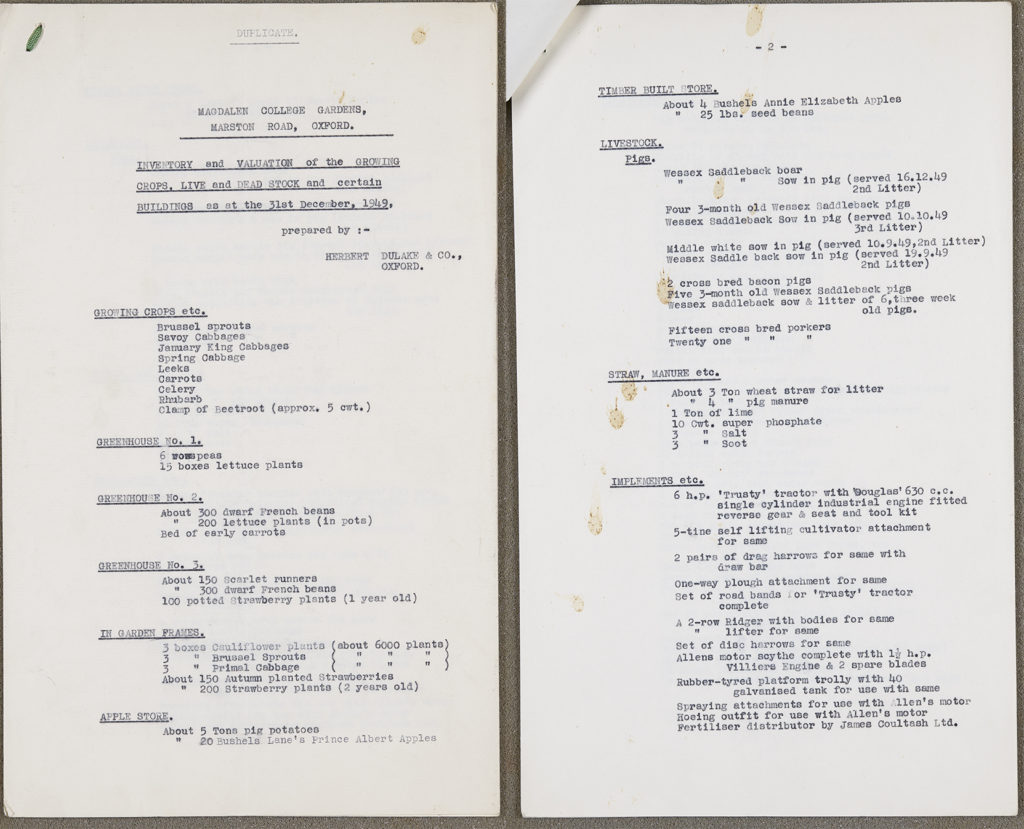

This inventory of the College’s agricultural concerns was lodged with the Governing body in 1949. In addition to recording the state of several pigs that had arrived earlier in the year, it details the use of College storage buildings for pig provisions. Magdalen College Archives MC:BUR/4/1

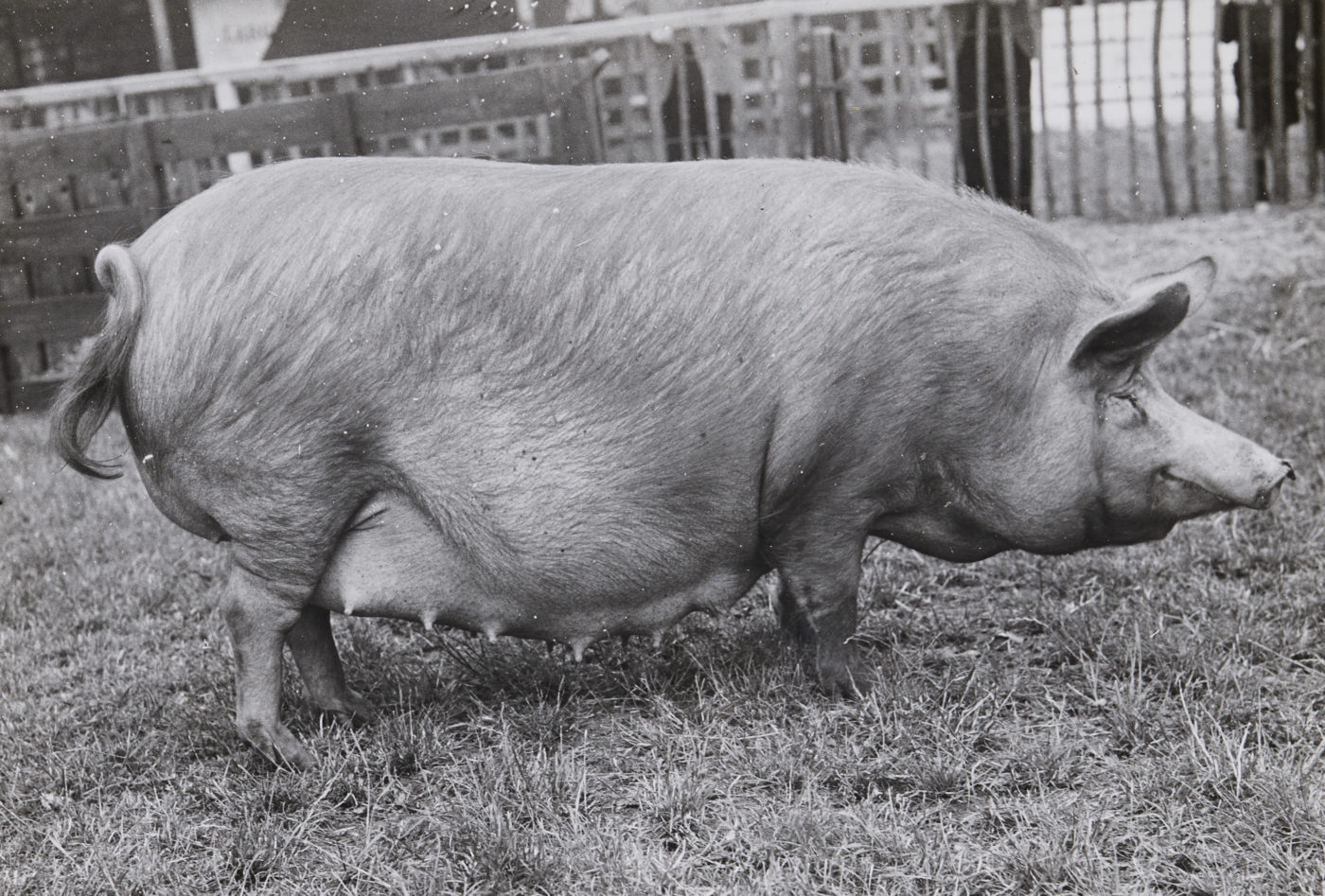

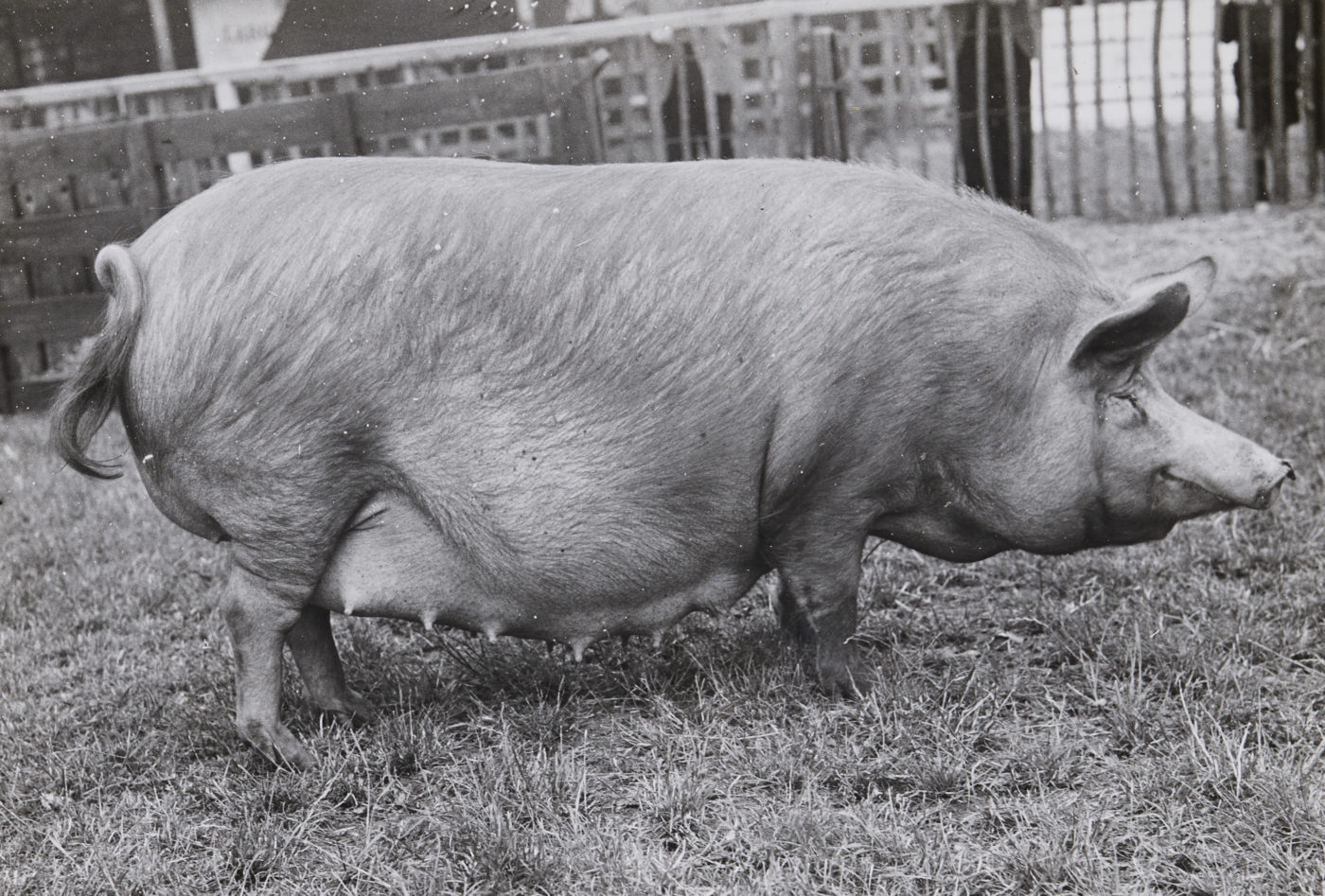

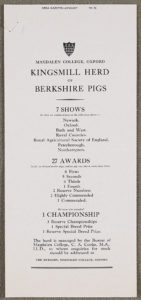

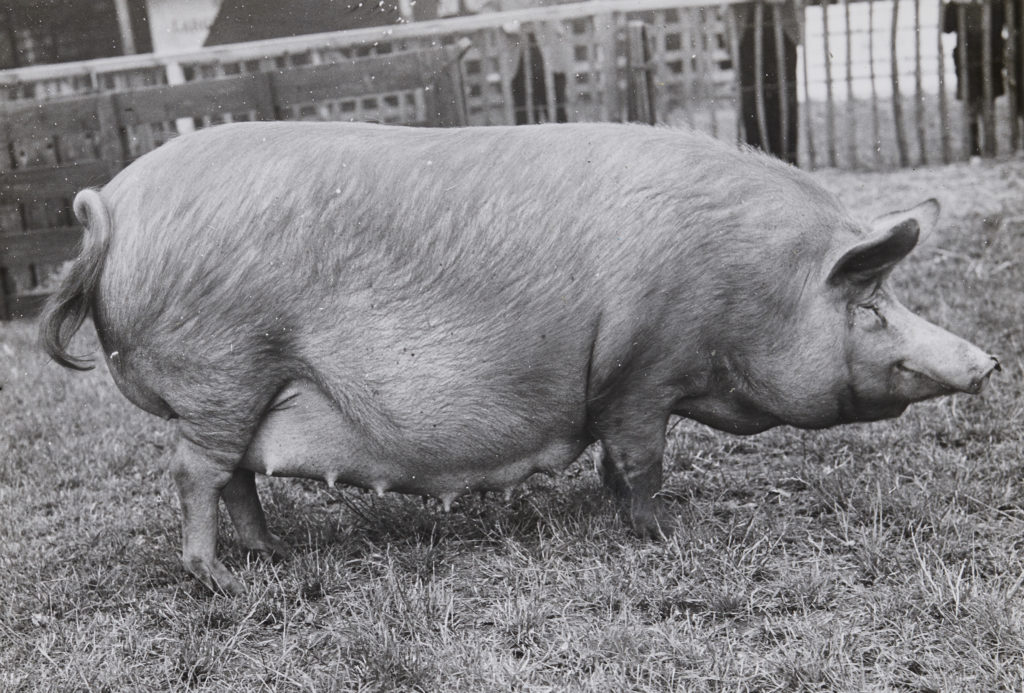

This advert ran in 1953, attesting the quality of the College’s herd of Berkshire breed pigs. Magdalen College Archives MC:BUR/4/4

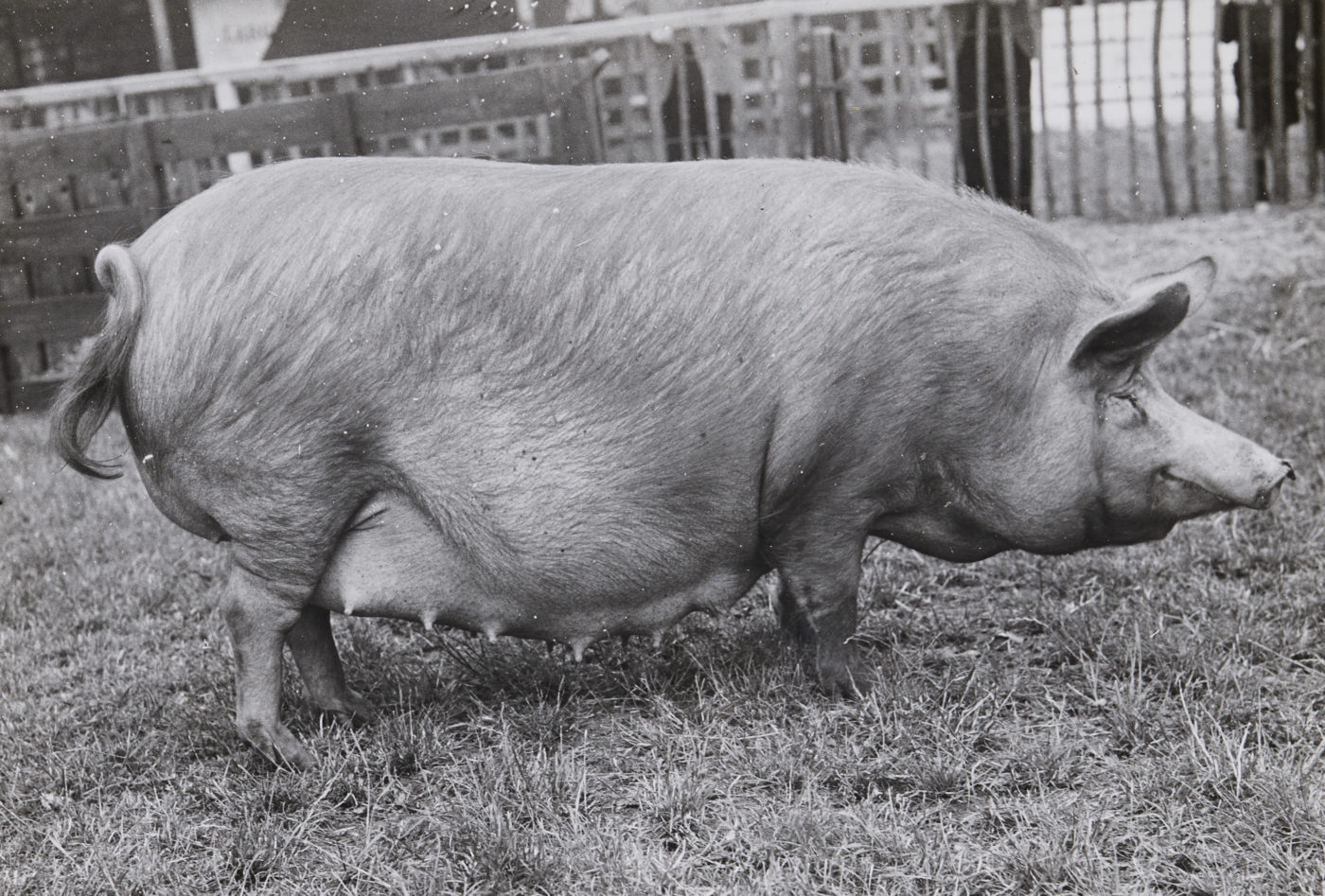

The College continued to use its extensive main site for commercial purposes well into the 20th century, growing various crops and keeping poultry on or adjacent to the College site. The efforts of Bursar Colin Cooke to keep pigs on the Kingsmill site (beside the Fellow’s Garden in the northeast corner of the main College site), seems to have been the last gasp for large scale animal work at the College. Despite being the end of College agriculture, Cooke’s pigs were remarkably successful, displayed at numerous agricultural shows and winning several awards. Magdalen pigs were even exported to the Continent and Argentina.

Magdalen College’s “Kingsmill Ballerina 15th” a champion female Tamworth at the Royal Show, Nottingham, 1955. Magdalen College Archives MC:BUR/4/7

Cooke was the driving force behind the enterprise, which seems to have begun with the arrival of the foundational swine in 1945. Documents detailing the College’s agricultural inventories show considerable resources dedicated to the pig-rearing operation, including the commandeering of the College apple store and mushroom house to store several tonnes of potatoes destined as pig feed. Production was sufficiently successful to merit advertisement of the Magdalen herd in the mid 1950’s; but by 1960 all farming activity in the College, pigs and otherwise, had ceased.

Missy the Harris Hawk, 2019

As Magdalen’s agricultural concerns dissipated, the College saw little in the way of ‘working animals’ on site until 2018. To combat the ever-growing population of pigeons trying to roost in Cloisters and other staircases, Magdalen now employs a professional falconer to run a Harris hawk weekly around College grounds. Harris hawks are natural deterrents to resident pigeons, however they are normally too slow to actually take a pigeon mid-flight. Missy (right) can normally be seen in Cloisters and New Buildings lawn being run by her keeper and letting the pigeons know that Magdalen is no place for them!